Veterans in college bring life experiences classrooms that may be unknown to many traditional-age students. Besides being older and having to balance jobs and families, vets share a tradition of service and sacrifice that’s as robust as any other culture on campus, advocates say.

Yet, veterans in college may have a hard time transitioning from the mission-oriented structure of the military to a more open, less rigid world of campus choices.

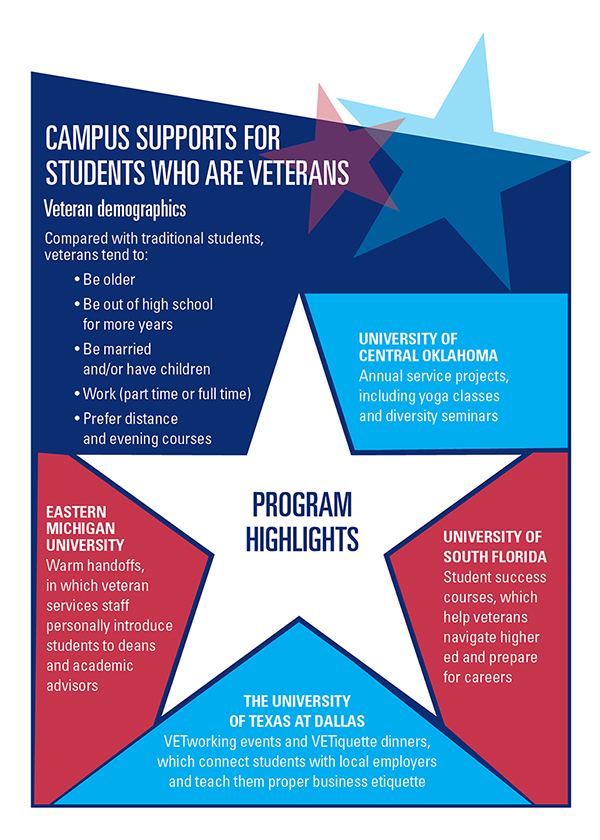

“In the military, you know what you’re going to do every day—it’s all mapped out for you—and then you come to a university and it’s chaos,” says Mark Kinders, vice president for public affairs at the University of Central Oklahoma, which Military Times ranked among the country’s top 10 campuses for veterans.

More on veterans in college: How faculty become ‘military competent’

That’s why faculty at a growing number of institutions are now more focused on supporting veterans in higher education. Faculty are learning to improve their communications with veterans, while administrators ramp up tutoring, financial and career planning, social programming, and other services for these students.

“Veterans are no different than any other group of students,” Kinders says. “If you get them engaged beyond the classroom, their likelihood of being retained to graduation goes up significantly.”

Launching yoga, promoting diversity

At Central Oklahoma, a federally funded student success program called SALUTE encourages veterans in college to spearhead campus service projects.

In 2019, veterans started military-specific yoga classes through the campus counseling center to help their peers with mental health and anxiety. For a 2018 “Heritage Series,” former service members of different ethnicities got invited to talk about how diversity has impacted their lives in and outside the military.

“SALUTE takes them from being a veteran who happens to be a student, to a student who happens to be a vet,” says Catherine Orozco-Christmas, director of the university’s Veteran Higher Education Resource and Opportunity Center.

Through partnerships with other university departments, SALUTE also funds student success services such as financial literacy workshops and graduate school tours. And about one-third of students using the GI Bill at Central Oklahoma pursue careers in education through the university’s College of Education and the national Troops to Teachers organization, Orozco-Christmas says.

Beyond its own campus, the university in supporting veterans in higher education by offering assistance to former service members headed to other four- and two-year institutions. It is also a host of the federal STRIPES-Veterans Upward Bound program. Staff members provide preenrollment counseling to any veteran who is disabled, a first-generation student or low-income, or has been out of school for five years.

The program served 130 veterans in 2018-19, and 125 in 2017-18.

The university has also become a source of expertise on veterans issues in Oklahoma, which has the 10th-largest population of veterans in the country. Work by several university departments resulted in new state legislation that has improved veterans’ access to health care, says Kinders.

‘Not there to mess around’

When applicants to the University of South Florida identify themselves as veterans, admissions coordinators are alerted and can ensure that these prospective students are contacted by support staff.

The Tampa-area university has made that communication with a priority for supporting veterans in higher education. Over the past 10 years, its Office of Veteran Success has grown from two staff members to a dozen full- and part-time employees, along with 30 students in the work-study program.

“Once you can show university leadership how many veterans you have and that you’re tracking them, it becomes easier to ask for resources,” says Larry Braue, the retired Army lieutenant colonel who directs the office.

Along with a veterans-only orientation, resources for veterans in college include two upper-level student success electives. The first course guides incoming veterans through academic planning, study skills and maximizing GI Bill funds.

More from UB: 5 steps to building virtual services for online students

The second class focuses on employment opportunities. Experts from the region are supporting veterans in higher education by helping the students prepare rÁ©sumÁ©s and practice mock interviews. Instructors also direct veterans to regional job networking events, Braue says.

As for academics, his office hires veterans to tutor other veterans. It also hosts social events, including football tailgating parties for military-connected families and an academic awards ceremony.

And its programs extend beyond veterans. Faculty, staff and other students can participate in training programs that help them understand military culture, Braue says.

“A number of faculty and staff have no idea what military life is like,” he says. “But veterans’ life experiences can be beneficial to the classroom and also for other students. Veterans can be considered mentors. They’re in school to get the job done and get out; they’re not there to mess around.”

Consider competing interests, don’t overprogram

Recurring VETworking events at The University of Texas at Dallas bring corporate recruiters to campus to connect with veterans and their spouses or partners. But the career-focused play on words doesn’t stop there.

Every other year, the university invites veterans and recruiters to a multicourse VETiquette dinner. Veterans not only get to do additional networking, but also brush up on using proper manners for a business meal—such as how to plate food and pass bread.

Services for veterans in college are guided, in part, by an advisory council that regularly examines the climate on campus and how it can be improved. The Peer Advisors for Veteran Education program, for example, pairs first-year students with older veterans. Another initiative, called Green Zone training, instructs faculty and staff on the characteristics of military culture and the challenges of transitioning to civilian life.

“When you tell veterans something, they’re going to do it; in fact, they may be looking for professors or faculty members to be more authoritative,” says Lisa Adams, director of the university’s Military and Veteran Center.

Adams says her office doesn’t overprogram students because veterans often have families and jobs that also demand their time. Carefully planned events include several service projects each year, which interest vets at her school.

Considering that two-thirds of veterans in the U.S. are first-generation students, Adams’ teams also help prospects and students with academic planning and goal setting—even if that means sending them to another college or university better suited to their career needs.

How to change hearts and minds

Eastern Michigan University’s veterans center, which opened in 2014, has the relaxed feel of a USO military lounge at an airport, says Michael Wise, assistant director of military services.

The Lt. Col. Charles S. Kettles Military and Veteran Services Resource Center (named after an alum and Medal of Honor recipient) is within a building that houses other student services offices and is located on a quiet part of campus, away from the hustle and bustle of the main student center. It offers complimentary

refreshments and a computer lounge.

Seeing staff doesn’t require an appointment. “Anytime a new face comes in, they get the red-carpet treatment,” says Wise, a retired Army lieutenant colonel.

Services for supporting veterans in higher education start with helping new students—whose average age is 25 to 27—make academic plans geared toward their majors. Once complete, Wise’s staff doesn’t just ship each student to the appropriate college. “We do warm handoffs,” he says. “It makes all the difference in the world to walk a student across campus and introduce them to somebody.”

Staffers also find course credits that students can be awarded for their military experiences.

Because veterans in college are often further down the life path than younger students, Wise’s office also helps them with home-buying and long-term financial planning.

But Wise and his staff are also supporting veterans in higher education by offering guidance on softer skills. For example, political discussions in class can sometimes anger veterans—particularly when 18- or 19-year-olds who have never served in the U.S. armed forces offer opinions on military operations.

“We encourage veterans to keep the dialog open and try to change hearts and minds,” Wise says. “If you feel you have an experience about which the younger student has not a clue, kindly, and in academic way, school them a little bit.”

Matt Zalaznick is senior writer.