The University of Minnesota system is internationally renowned for its sustainability initiatives and research, reducing greenhouse gas emissions by 50% between 2008 and 2022. Its 2021 strategic plan, MPact 2025, only upped the ante, promising to reduce emissions by another 60% by 2033 and become carbon neutral by 2050. This work closely aligns with the mission of the United Nations’ Sustainable Development Goals.

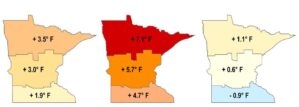

The Twin Cities campus’ 2023 Climate Action Plan set a concrete plan in motion on reducing emissions across campus and the recently unveiled Climate Resilience Plan outlined this year has expanded the R1 university’s efforts on how they can address the effects of climate change on its infrastructure and environment right now. Minnesotans experienced the 10 warmest and wettest years in the state since 1998, and the state has experienced a significant uptick in extreme, large-area rainstorms that are projected to increase.

“[Minnesota] is sometimes recognized as a climate haven, but we too have our impacts from climate change,” says Kate Nelson, director of sustainability on the Twin Cities campus. “By digging further into those scenarios, we can better plan around our priority areas.”

Source: Minnesota Department of Natural Resources

Nelson is concerned about how these extreme temperatures can affect the Twin Cities’ most under-resourced and marginalized communities that are more likely to work labor-intensive jobs outside. “Sometimes we have a one-off, 100-degree Fahrenheit day, but what if we have a 95-degree day for seven days? What if we have consistent rainfall over one inch a day for a month?” Nelson says. “It’s not just about hazard planning, and that’s something resilience gets at that not a lot of planning does.”

A university survey showed that 80% of the system’s community agreed climate change is extremely or very important to them, and its 2021 strategic plan states that fighting climate change is a key priority to create a fully sustainable future.

More from UB: Here are 2 developments that could compromise the DOE in the next year

With temperatures rising, campus trees are more susceptible to contracting diseases that thrive in the heat, thus decreasing the natural canopy available to protect students from the harsh sun rays. As a result, the R1 university is researching which trees can withstand the environment and shade students and staff. As for increased downpours, the university is identifying areas of campus most prone to flooding and water damage.

Twin Cities is also inviting members from underrepresented communities into its climate task force who can help cover blind spots in research and implementation. “It’s not just about the action, but how can we measure [climate change’s] impact and get solid feedback,” Nelson says. “You always have to ask yourself whose voice is at the table and whose is not.”

The obstacles of a climate change trailblazer

Twin Cities wants to ween off traditional fossil fuels while maintaining optimal emergency generator functionality to protect its IT infrastructure and laboratories hosting delicate biological samples. They are currently exploring Kohler energy and hydrogen resources, but the contrasting time scales of different university stakeholders can hamper the process, Nelson says.

“We’re working on building an intentional relationship between the operational changes that need to happen and those who are championing research strategies and the student learning opportunities that exist,” she says. “Implementation versus the timeline of research tends to not align.”

Moreover, the university faces ambiguity in improving building resilience because there aren’t any official standards from facility planners. Nelson’s team is now collaborating with the university’s Center for Sustainable Design to develop solutions while also adhering to state sustainability standards.

A big source of inspiration for the Twin Cities campus is the 2022 climate and resilience plan at the University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee, which Nelson helped develop as its former sustainability director. Because the two universities live in neighboring states and share similar climates, it’s easier to build off each other’s work. However, universities in other regions, such as South Florida, will have different indicators of success depending on their vegetation and climate benchmarks.

Trailblazing the climate resilience space comes with the cost of going at it alone with minimal resources. However, Nelson believes it’s necessary to provide future universities with a stepping stone to work. “We are facing these hazards faster than we thought, but I would say that to tackle an emergency, we must go slower,” Nelson concludes. “We must include more people, we must be more thoughtful. I hope this plan opens up the space to do that.”