As academic videos have become mainstays in college classrooms, faculty are increasingly turning to instructional designers to help them engage a generation of students who have grown up watching YouTube.

The popularity of academic videos has risen as the number of online, blended and flipped classes has soared on college campuses, fueling the demand for instructional designers. At least 13,000 instructional designers now work on U.S. college campuses, according to a 2018 report by the Online Learning Consortium. That number is expected to grow as enrollment in online and blended courses continues to climb.

Instructional designers guide faculty in converting their face-to-face courses to online formats. State-of-the-art academic videos are a critical piece of that transition. “In online courses, videos roughly hold the spot that textbooks used to hold,” says Malcolm Brown, director of learning initiatives for Educause. That is also the case for many traditional courses, he adds, because of “the sinking boat of classic textbooks,” which are often being replaced by open educational resources, he adds.

Here’s how instructional designers are advising faculty on academic video content and production.

Ensuring faculty understand instructional video basics

The best technique for creating instructional videos is now considered tried and true: break them up so that students can view smaller chunks of information. One MIT/edX study of students watching videos in four massive open online courses concluded that six minutes is the ideal length, with student engagement declining as videos get longer.

Yet sometimes, professors still want to film an entire class, says Constance Harris, director of online learning at The University of Baltimore. She advises faculty to pull the content that’s going to be most meaningful to get the point across. In online classes, professors can use video to create a more personal connection with students. They can introduce themselves at the beginning of the course and record a summary of each week’s material.

“Video is a way of instilling that instructor presence,” says Stephen Bridges, instructional designer and lead media producer at the University of Georgia. “The faculty member is a person with whom I’m interacting, and there’s not just a robot on the other end of the internet.”

In flipped courses, the videos students view as homework must focus on the next day’s activities. And in brick-and-mortar classes, professors are also using video to enhance the learning experience. Videos in a traditional classroom might show a professor demonstrating how to conduct a lab experiment or interviewing an expert at a remote location. “Faculty can disseminate information much easier that way,” says Dawn Dubriel, an instructional designer at Lynn University in Florida. “And it’s the way students like to learn.”

5 tips for producing the best instructional videos

1. Make sure the video has a specific purpose that relates to the learning objectives of the course.

2. Use video to establish a presence for the instructor by introducing the faculty member at the beginning of the course.

3. Create video segments of no more than six minutes each.

4. Add interactive elements to the video, such as a quiz or recorded discussion board.

5. Make sure the video is accessible to students who are visually impaired.

Guiding faculty through video production steps

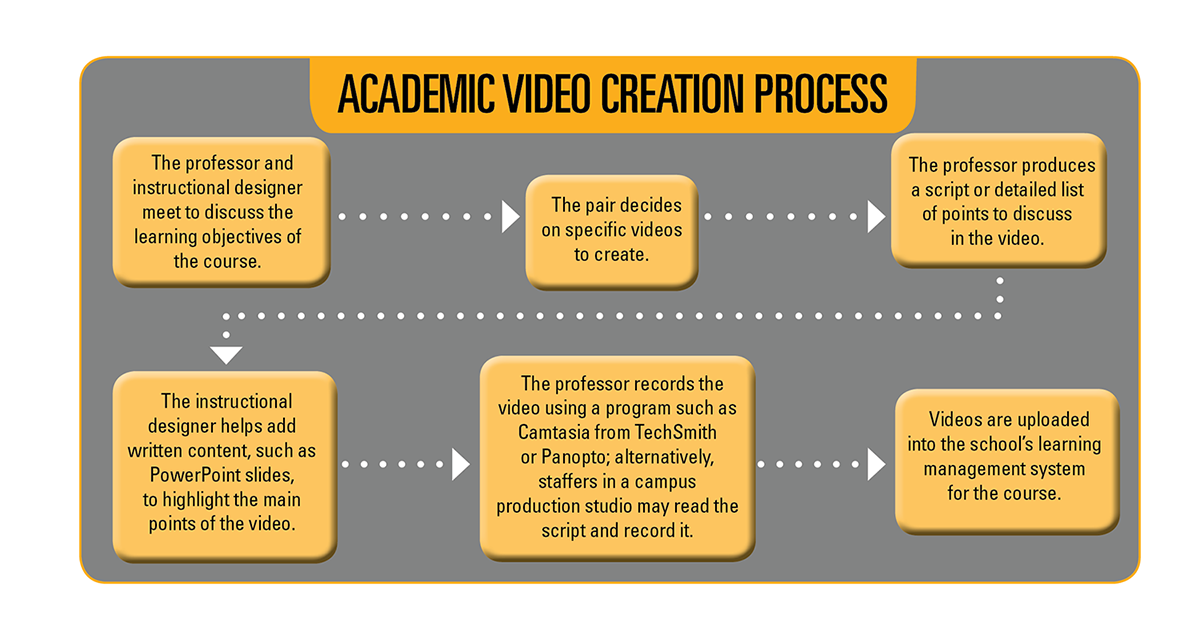

Creating an academic video requires collaboration between the instructor and the instructional designer. It often begins with a conversation about the course’s goals and how video can enhance the learning objectives. After discussing specific types of video projects, instructional designers generally recommend that the professor write a script, or at least a bulleted list of specific items that identifies what to cover. “It will help them know how long the video will be, and they won’t get project creep,” Bridges says.

While some colleges and universities have large staffs of instructional designers who create videos for professors, others rely on faculty to produce videos themselves. “What you really want is a model that is sustainable,” says Harris of Baltimore. “The best model is to teach faculty how to create their own videos, so if they want to create a video, they can do it whenever they want to.”

At Rochester Institute of Technology in New York, four instructional designers consult with professors, who then use Camtasia video software to record voice-over PowerPoint presentations and short lectures. “We talk to them about best practices and make sure that each video has a very specific point,” says Marty Golia, instructional design researcher and consultant at RIT.

At Lynn University, Dubriel uses a combination of approaches, including producing videos with professors and showing them how to do it themselves with recording software. “I like to teach them how to fish so I don’t have to do every single one,” Dubriel says.

Once a lecture is recorded, instructional designers encourage faculty to add an interactive quiz or activity that allows students to apply the content they’ve just viewed. For example, students might be asked to record a critique on the video itself or a response on a discussion board.

“That’s a common aspect of human learning psychology. Once you’re introduced to an idea, reinforcement is important,” says Brown from Educause.

Helping faculty with more complex academic videos

Going beyond voice-over PowerPoint presentations typically involves having studios staffed by teams of instructional designers, technical editors and multimedia experts. These production studios often have the capability of shooting video for faculty at remote locations.

For the “Current Issues in Public Health” course at Johns Hopkins University, for example, an instructional designer created a video that recorded a tour of Maryland’s Office of the Chief Medical Examiner. It included an interview with an employee whose job was to prepare the deceased on a daily basis at the state morgue. “That’s a level of authenticity that you just can’t get without video,” says David Toia, video production supervisor at the Center for Teaching and Learning at the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health.

Related at UB Tech®—Brian Klaas, senior technology officer at Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health, presents on Creating a Culture of Inclusion and Accessibility in Digital Environments. Session details, and more on Klaas’ talk

A new type of video produced at the School of Public Health records multiple Skype interviews of experts, which are then presented simultaneously on the same screen. Created with a production system called a TriCaster TC1 from NewTek, the new video type is similar to the multiple-interview format used on CNN, Toia says.

With a staff of 36 people, the Center for Teaching and Learning expects to produce about 200 videos this academic year. “When you talk about scalability, we operate like a news organization,” Toia says. “We have to work at that volume.”

Creating a video with the Center for Teaching and Learning begins six to nine months ahead of the start of a course.

That is similar to the time frame followed in the Online Learning Fellows program at the University of Georgia. The program works with faculty over a nine-month period to develop online summer courses and create embedded videos.

One course Bridges helped develop through the program is “Tombs and Temples,” which introduces students to the world’s most famous archaeological sites. The professor teaching the course recorded several demonstrations, such as fire building and spear throwing, on a video produced using a lightboard, a glass surface the instructor stands behind and writes on with neon markers. The lightboard uses a mirror to reverse the image so that the instructor’s writing can be read by the viewer.

Lightboard videos, which are available through an open-source platform, are complicated to produce. They require an elaborate studio setup that uses a special type of glass, which is cut in a 4- by 8-foot sheet and is lit internally by bright white LEDs.

Apps and websites, however, are now available that faculty members and instructional designers can leverage to record their own high-quality videos without the help of a production studio. “As technology gets easier to use and more and more affordable,” Bridges says, “it’s only going to make it easier for faculty to create videos themselves.”

Sherrie Negrea is an Ithaca, New York-based writer and frequent contributor to UB.