A car accident at Lehigh University—or rather the damage it did to the Pennsylvania school’s property—remains a topic of debate even more than a year later. The tire tracks were filled in long ago, but the repair of a damaged abstract sculpture hasn’t been a simple fix. “We had a really difficult time finding out the exact value and how to fix that item because there are very few individuals who actually fix pieces of art to make them look right again,” says Kim Nimmo, the university’s director of risk management.

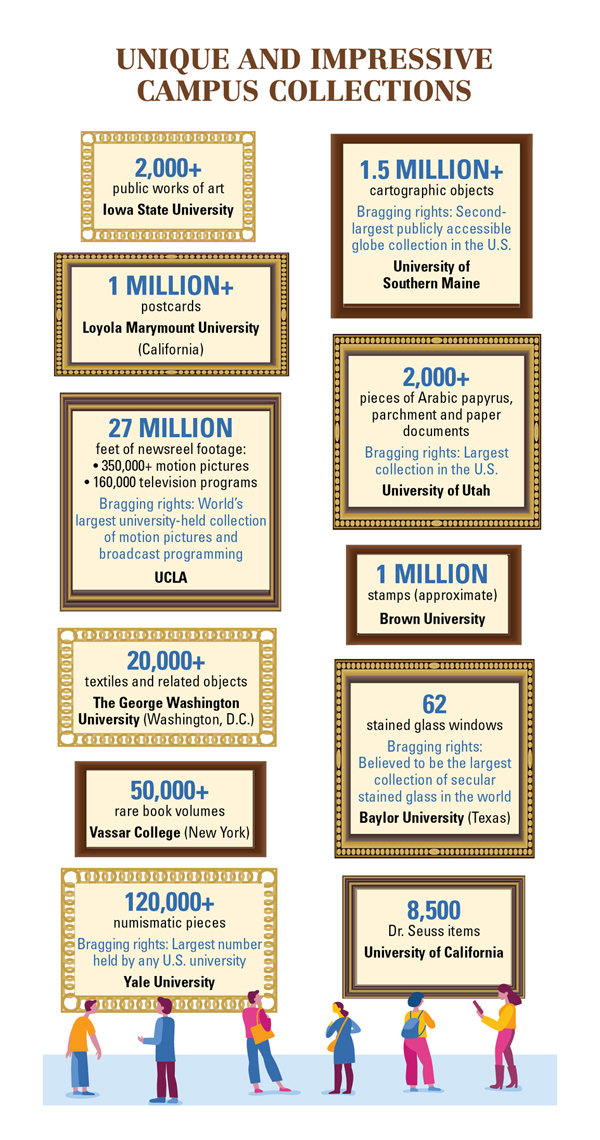

Lehigh’s challenge isn’t unique. Campuses across the country hold thousands of valuable items, from works of art to rare books, coins, clothes, films and a host of other materials. All require insurance coverage that invites various considerations for university administrators, curators, library directors, risk managers, development officers and beyond.

The following questions can help decision-makers think about how their campus valuables are insured.

1. What is the purpose of the insurance plan?

Each institution will have a different need when it comes to maintaining insurance for items, depending on what valuables are being insured and how much they’re worth. Many institutions choose to cover their valuables through a blanket or umbrella policy with a property carrier, while others select specific policies that cover, for example, a particular area, such as fine arts.

Each policy will have its own exclusions and claim limits. When choosing coverage, officials should determine not only what may need insuring, but also why that insurance is necessary.

At the Rhode Island School of Design, administrators conduct those discussions with an eye toward allowing the school “to rebuild a collection that supports the mission of the institution” in the event of a major loss, says Jennifer Howley, risk and emergency manager.

Considerations about replacing damaged items, repairing them or letting go of portions of a collection that don’t fit into the university’s mission should become part of the larger insurance conversation. Those decisions will come into play when a claim must be made.

“There is a moment of ‘let’s jump to the quickest solution,’ and sometimes that’s not the best answer,” adds Nimmo, of Lehigh.

2. What valuables does the institution own?

Blanket higher education insurance policies don’t necessarily require an inventory of every item held. However, it’s good practice to keep precise records.

“Get very familiar with all corners of campus; know where things are located and who is managing them, and keep an inventory,” Howley says. Two common collection management software options include TMS Collections from Gallery Systems and MuseumPlus from Zetcom.

Yale University’s risk manager organizes an annual review of all valuables held across campus, asking the various departments questions about what they’ve acquired, best practices in place for securing the inventory, planned exhibitions, collection values, and outstanding or planned item loans. The risk manager then submits the information to the insurance carrier.

Knowing what valuables exist extends to establishing a communication policy, as well as a chain of command for what happens when an item is donated or procured. “If we don’t know about it and something occurs, it’s a really difficult job to peel back the layers and figure out where it came from. It slows down the whole claim process,” says Nimmo.

3. How will items be valued?

As Lehigh’s sculpture repair case makes clear, how an item is valued is critical both for ensuring adequate coverage and for making a claim in the event of a loss.

Valuing some items, especially those considered rare or priceless, is subjective. Insurance policies should dictate how items are valued and align with coverage. Some schools choose to use the current market value of the item at the time a claim is made, others rely on curators to make an appraisal, and still others make a decision based on the donor’s stated value of the item when it was procured.

4. How can valuable items be secured to limit claims?

The Yale University Art Gallery—like most campus museums across the country—follows museum standards when it comes to protecting items. When considering how to store or display a valuable, “our first consideration is the safety of the object,” says L.Lynne Addison, the gallery’s registrar.

Questions include:

- Is the item vulnerable?

- Does it need plexiglass or glazing in front of it?

- Should it be on a platform so you can’t reach it? Should it be under video surveillance?

- Should there be an alarm on it?

Every object will have a different requirement based on its size and location and on its aesthetics and accessibility.

Addison says the art gallery rigorously secures all of its objects no matter the value, but adds that once “you hit $5 million, $10 million or $15 million, you start thinking a little differently.”

Security also requires some give and take among those involved in decision-making. Protecting pieces is an “interesting balance,” Lehigh’s Nimmo says.

For example, while an insurer might want an entire building to be equipped with a fire suppression system, those responsible for the valuables might not agree, given that water and precious items don’t mix.

“You have to pick your battles. Do you want to protect the building or the piece?” he adds.

The right balance becomes even more difficult when dealing with populated buildings or buildings that store valuables along with hazardous materials. Further, a large quantity of valuables may be stored in one location, increasing the risk that a natural or human-made disaster can result in a significant loss and subsequent claim.

Related: Insuring items on loan and in transit

“This makes insurance carriers and me nervous because I’d like to spread it out, but I can’t because we don’t have the room,” says Nimmo. Security can also extend to who knows what the institution has in its buildings. “You’re not walking into Fort Knox. Almost anyone can get in and out,” says Nimmo.

Some universities that hold controversial or rare valuables choose to keep knowledge of their existence limited.

5. Who needs to be involved in insurance conversations?

How a piece is transported, stored, secured and displayed requires extensive conversations among stakeholders both on and off campus. They often include risk management staff, general counsel, development office staff, facilities staff, department heads, curators and library directors—each bringing a different perspective to the conversation that cannot be overlooked.

“Everyone needs to understand their role. Someone in facilities may not be the best person to decide where or how something should be stored,” says Nimmo. Yet such an individual is often responsible for building control and must be consulted. “You need a teamwork process to make this work,” he adds.

Looking off campus, many colleges and universities opt to partner with insurance brokers who specialize in certain types of valuables. Lehigh administrators work closely with a broker who has connections to fine arts and property carriers that help them understand how to interpret the existing insurance policy and how it applies in different situations.

Also read: Cyber insurance checklist: 4 ways to avoid missteps in purchasing

“We can do all the legwork here on campus; we can get it moved in, move it around, store and protect, but when it comes to the fine print and some of the legal work, we work closely with our broker,” Nimmo says.

Ensuring a good working relationship with all interested parties is critical. By maintaining these relationships, says Yale’s Addison, “everybody understands how much this means to us, and so everybody works really hard to protect our objects.”

Heather Kerrigan is a Washington, D.C.-based writer.