COVID-19 has hit higher education like a tsunami. Across the country, instructors and students have rapidly cleared out of their offices and dorms and just as quickly sought to transition to online learning.

This unprecedented shift raises two important questions: Can quality education be achieved in these circumstances, and can it be equitable?

Is online education equitable?

There is a lot of reason for skepticism. Our research conducted at a range of institutions shows that students tend to suffer online performance decrements, such as lower course completion rates and lower grades. And more disturbing, these gaps between face-to-face and online achievement are larger for low-performing students than for high-performing students, and they are also greater at broad, public-access institutions, including community colleges, rather than at elite universities. For all of these reasons, the growth of online learning can hamper efforts for educational equity.

Read: How to create community in online learning

Our research also shows the roots of these problems, which lie in the inherent structure of online instruction. Online classes, which are often based on “learn on your own time,” require more autonomous learning skills than face-to-face classes. Students, especially those who are low performing, often lack the self-regulation and study skills necessary to succeed in unstructured online environments.

In addition, online classes have fewer opportunities for direct interaction between the instructor and students, or among students, than face-to-face classes. Students often feel socially isolated and have a hard time connecting with the instructor and their peers online. Without these connections, they may have difficulty understanding course requirements and content, and become disengaged, confused and discouraged—again, especially students who are already at risk.

If we pay careful attention to a few basic principles of how to support student learning online, we can both limit the harm and develop the pedagogical approaches that will best serve our students in the future.

Overcoming online achievement gaps

Fortunately, our research also shows five important steps instructors can take to overcome these challenges, with benefits for all students, especially those who are most at risk in online environments.

- Create clear course syllabuses and materials, with simple but detailed explanations of how to navigate the course, access materials, participate in class activities and submit assignments.

- Humanize the course by showing your face and personality, communicating frequently with students, and giving students multiple channels to communicate with you.

- Promote social interaction among students by having them introduce themselves, engage in group discussion and collaborate on group projects.

- Teach students the study skills that are especially valuable for online learning, such as how to plan their study time, the importance of spacing out their study, and techniques for self-assessment.

- Support students’ self-regulation through frequent reminders and nudges in multiple ways throughout the term.

Read: How to transition (quickly) to online instruction

Resources for online instruction support

Of course, recognizing that these steps are valuable is not the same as being able to implement them in instruction, especially during periods of rapid transition to online learning. For that reason, we created the Online Learning Research Center to guide instructors through implementing changes. In each of these five areas, we explain why improvements are needed; discuss how to make them; and point to a carefully selected set of resources, including examples, materials and templates.

Additional features of the OLRC website include links to our research papers on each specific topic; an evidence-based rubric of quality online instruction so instructors can reflect on their courses; a separate set of guidelines for instructors who are just beginning online instruction; and resources for students to develop their study and self-regulation skills.

Read: New to the higher ed digital community?

COVID-19 is placing huge challenges on our nation and the world. Unfortunately, we can expect that the emergency transition to remote instruction will harm the quality of instruction in the short term. However, with or without these kinds of emergencies, online learning has been growing steadily for years, and is expected to continue growing in the future.

If we pay careful attention to a few basic principles of how to support student learning online, we can both limit the harm and develop the pedagogical approaches that will best serve our students in the future.

Read: Updated: 37 free higher ed resources during coronavirus pandemic

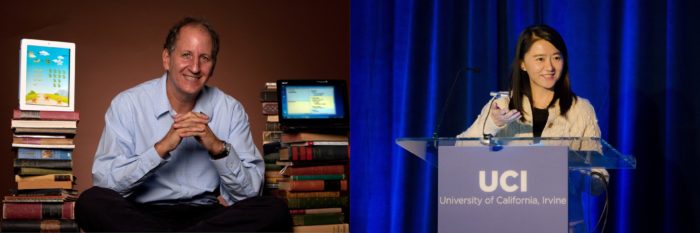

Mark Warschauer is a professor of education at the University of California, Irvine. He is a member of the National Academy of Education. Di Xu is an associate professor of education at the University of California, Irvine and a research affiliate at the Community College Research Center at Teachers College, Columbia University.